26 August 2025

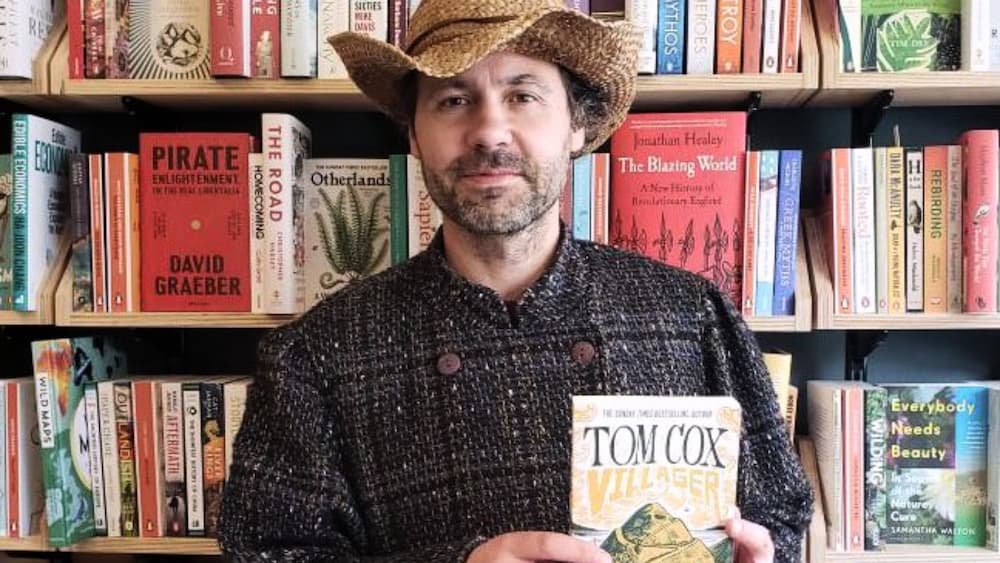

Tom Cox was born in Nottinghamshire, now lives in Devon and is the bestselling author of fifteen books of fiction and non-fiction. His debut short story collection Help The Witch won a Shirley Jackson Award and his 2017 book 21st-Century Yokel was long listed for The Wainwright Prize.

Tom’s debut novel Villager is one of our selections for Wild Reads 2025. Tom will be in conversation with Lisa Brennan on Thursday 4 September for an exclusive online author talk, which is free to register. You can find Villager and Tom’s other books on the সাফোক কমিউনিটি লাইব্রেরি ক্যাটালগ.

What was your first introduction to books and reading? Were you surrounded by books as a child or did you visit a library?

I remember – from pretty much the moment my mum and dad first read to me – that I couldn’t get enough. I’d nag them for “just one more story, pleeeeaaaase” way after my bedtime (I fictionalised this habit in my second novel 1983). I also remember that they could leave me for hours in the two main libraries we used in Nottinghamshire – Eastwood and West Bridgford – and I would do anything but complain. After that I had a very sporty adolescence and read very little, but as soon as I broke out of that strange fugue, at around 17, I was determined to catch up and get back on track.

প্রকাশনার পথে আপনার যাত্রা কেমন ছিল?

If you mean in the sense of my first book, I was fortunate to have a fairly high profile newspaper job (as The Guardian’s Music Critic) and to have been, at 25, writing in an era when publishers and agents came looking for authors a bit more (as opposed to the other way around, which is far more commonly the way now). Although those agents and publishers were a bit surprised when I said the book I was writing was about golf. Since then, it’s been a very up and down ride, covering many subjects. I feel, in a way, that my first eight books were sort of “training wheels” books where I was still finding my voice, still learning to be brave enough to write what I really want to write. 21st-Century Yokel, in 2017, felt like the start of my real career as an author, and the next six have followed on from that. I still feel like I’m just getting started

What is your writing routine? You said in Ring the Hill that ‘everything is research if you want it to be’. How does that work in creating a book like Villager?

I have an idea, which is to get up at somewhere between 5am and 6am and bottle the writing energy I always have then (it’s possible that energy might just be caffeine, but it’s still useful, whatever it is!) and spend the late afternoons and evenings more in reading/writing research mode. In reality, it’s often all a lot more chaotic than that. A lot of my best thoughts come to me on walks, and this has never been more the case than with my walks on Dartmoor and the way Villager came together, kind of like I wasn’t writing it at all, and was just pulling it out of the sparkly upland mist. My job was just to make sure I didn’t pull too hard and break the invisible string that was attached to it.

Do you explore places before you write about them or do the places inspire the stories?

I’m always looking for new places to explore. And that doesn’t just mean walking in beautiful places. I like to check out new places which a lot of people would call ugly or desolate too. Everything is interesting if you look at it from the right angle.

Villager has been chosen as one of our Wild Reads books this year. Can you tell us a little about it and how you came to write it?

I’d been wanting to write an episodic, folkloric novel about the countryside for many years. Initially, I wanted to set it in Norfolk (where I lived between the autumns of 2001 and 2013). I kept starting then abandoning it, again and again, blaming it on life getting in the way, having to do “proper writing” (journalism, back then) to pay my rent or mortgage, or just people not being interested enough. But the truth was that I simply did not yet have the experience or the emotional tools that I needed to write the kind of book I wanted to. So it was a waiting game. I wrote, I failed, I learned, I walked. Then, finally, in the summer of 2020, it was really a case of “If I don’t actually do this thing now, I’m not going to be able to forgive myself.” From the first sentence, I found out I was ready. And the story told itself.

ভিতরে Villager the landscape itself is a character. Was this something you planned or did you go where the story took you?

Very much the latter. I looked at Ugborough Beacon, on the southern edge of Dartmoor – a hill I’d long been fascinated by, and which I’d walked up in 101 different kinds of weather – and then across at its neighbour Brent Hill (a former volcano) and thought, “What if one of these hills had a face, and could see us all, with our silly little lives, below it?” Then I wrote the first sentence of the book.

RJ McKendree is a key figure in your story, and he even has his own album Wallflower. How did the collaboration with Will Twynham come about?

I’d already had a soundtrack for one of my books, Help The Witch, from 2018, which involved ten different artists writing their own musical response to one of the book’s stories. I fancied doing something similar for Villager, but then chatted to Will about it, and we soon realised that, with Wallflower being such a central part of the book, it would make far more sense to record that. Will made it very clear that he wanted to do it all himself, and he’s so absurdly talented, and knowledgeable about mid-late 60s music, I knew he’d make a phenomenal job of it. But he exceeded all expectations. I wish more people knew the soundtrack (and Will’s other music, under his other alter ego, Dimorphodons) existed.

তোমার জন্য এরপর কী?

My ex-publishers, Unbound, stopped paying their authors last year, including me, then went into administration, which has cut horribly into my creative time this year, and means I have the most insanely huge backlog of stories I want to get on paper. Fortunately I have a new publisher, Swift Press, now, who published the paperback of my second novel 1983 on August 14th, and will be publishing the hardback of my latest novel Everything Will Swallow You in September. Then it’s a matter of which of the other three projects I’m in the early stages of punches its way through and shouts “Me first!”

Wild Reads is all about nature and our relationship with it. Who are your favourite nature writers?

I fear my answer might be a little disappointing to some here, in that most of the people whose writing about the natural world that I love most are people who do that outside the genre of what people generally call nature writing. A love for nature and a mourning for the landscapes and wildlife we have lost is present in the books of, for example, Annie Proulx, Cormac McCarthy, Tim Gautreaux and Denis Johnson, but none of them are thought of as “nature writers”.

At the same time, I’m also hugely pro nature writing, since I’m hugely pro anything that gets people thinking more about our relationship and duties to the landscape around us, especially if is helping to open previously closed eyes. John Lewis-Stempel is fantastic, I think, and Common Ground by Rob Cowen is probably the most unusual, brave and interesting nature book I’ve read.